A recent string of revelations about abuses by the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps presents an opportunity to rein in the military’s presence and power in public schools.

01.08.2023 / Seth Kershner Scott Harding / Jacobin - The Pentagon’s signature program for instilling military values in American schools, the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC), has a long history dating to 1916. But it hasn’t endured such bad press since the 1970s. In several damning articles, the New York Times revealed the structure of what’s wrong with high school military training: instructors who use their positions to prey on teenage girls, in-school shooting ranges built with grants from the National Rifle Association, and mandatory enrollment in some of the nation’s largest school districts — all abetted by school officials who fail to adequately monitor a program of such dubious educational value that many instructors lack a college degree.

01.08.2023 / Seth Kershner Scott Harding / Jacobin - The Pentagon’s signature program for instilling military values in American schools, the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC), has a long history dating to 1916. But it hasn’t endured such bad press since the 1970s. In several damning articles, the New York Times revealed the structure of what’s wrong with high school military training: instructors who use their positions to prey on teenage girls, in-school shooting ranges built with grants from the National Rifle Association, and mandatory enrollment in some of the nation’s largest school districts — all abetted by school officials who fail to adequately monitor a program of such dubious educational value that many instructors lack a college degree.

These revelations have vindicated those in the “counter-recruitment” movement who for years warned of a largely unsupervised program taught by retired military officers. It also raises serious questions about why military training programs have any place in US public high schools.

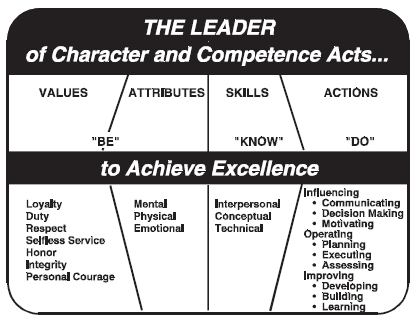

The Pentagon spends around $400 million annually to provide training in military drill and “leadership” through the JROTC in more than 3,500 high schools, to approximately five hundred thousand students. Despite this presence, the program seems to operate on the fringes, with school officials exercising scant oversight even as instructors take their young “cadets” on extended travel to military bases and interschool competitions. Such conditions foster an environment rife with potential abuse.

The Times identified at least thirty-three JROTC instructors who had been criminally charged with sexual misconduct with their students, and found evidence that numerous other instructors were accused but never charged. According to the education outlet Chalkbeat, Chicago’s head of school military instruction quietly resigned last summer, three years after failing to inform officials of suspected sexual abuse by a JROTC instructor who was later arrested.

Sep 6, 2022 / Aina Marzia /

Sep 6, 2022 / Aina Marzia /  September 28, 2022 /

September 28, 2022 /